I was reading a book called Patterns for Parallel Programming during my flight to Hawaii. It was a long flight, and I couldn’t sleep.

The authors’ targeted audiences seems to be the academic world. The content of the book is very dry. It has too much text and formulas, and not enough pictures. (and I like pictures!)

Anyway, in the design space section, the book briefly covered the Pipeline Pattern. Although the chapter is short, the implementation is very elegant, and the architecture is beautiful.

Here I attempt my C++ implementation following the spirits of the Pipeline Pattern.

The Basic Idea

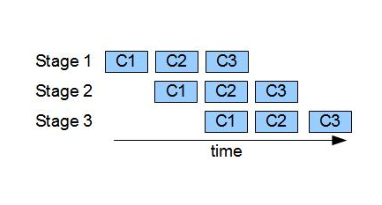

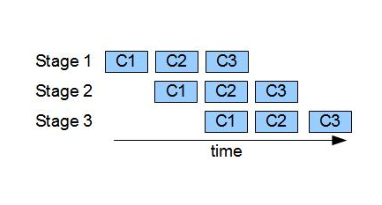

The basic idea of the Pipeline Pattern is similar to a processor instruction pipeline. A pipeline holds a number of stages. Each stage performs some operations and pass its results to the next stage. Since all stages are executed concurrently, as the pipeline fills up, concurrency is achieved.

C is a unit of work. First, C(1) will go through stage 1. When it completes, C(2) will go through stage 1, and C(1) moves onto stage 2, and so on..

To express it in high-level programming language, we can think of a stage that just grabs some work unit from the previous stage, perform operations, and output its results in the next stage.

// pseudo-code for a pipeline stage

while(more incoming work unit)

{

receive work unit from the previous stage

perform operation on the work unit

send work unit to the next stage

}

Since I am implementing the pattern in a OO fashion, stage will be expressed as a class. A pipeline, which consists of many stages, will be a class that holds an array of stages.

Finally, since stages communicate with each other by passing data, we need another data structure that supports this behavior.

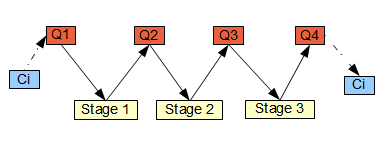

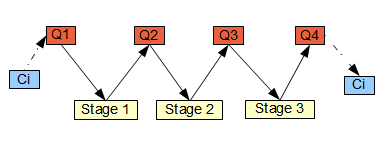

The author chose to use a Blocking Queue to connect the stages. Each stage will hold an in-queue and out-queue pointer. The in-queue of a stage is the out-queue of the previous stage, and the out-queue of a stage is the in-queue of the next stage. So it is a linked-list of queues.

Ci is the work unit to the computed. It will first be inserted to Q1. Stage1's in-queue is Q1, and out-queue is Q2. After stage1 completes its operation, it output the result to Q2. Stage2's in-queue is Q2, and out-queue is Q3. This continues until Ci goes through all stages.

So enough talking, let’s jump straight into the fun stuff.

Blocking Queue

First, we start with the smallest unit, the Blocking Queue. The behavior follow closely to the Java’s implementation.

The Blocking Queue allows two simple operations – Take() and Add(). Take() extracts input data, or blocks until some data is available for a stage. Add() simply adds data to a queue.

// some code and comments are omitted to save space, download the

// source to see the full implementation

template<typename WorkType>

class CBlockingQueue

{

public:

WorkType Take()

{

boost::mutex::scoped_lock guard(m_mutex);

if(m_deque.empty() == true)

{

m_condSpaceAvailable.wait(guard);

}

WorkType o = m_deque.back();

m_deque.pop_back();

return o;

}

bool Add(WorkType const & o)

{

boost::mutex::scoped_lock guard(m_mutex);

if( (m_deque.size() >= m_maxSize) &&

(NoMaxSizeRestriction!= m_maxSize) )

{

return false;

}

m_deque.push_front(o);

m_condSpaceAvailable.notify_one();

return true;

}

private:

boost::uint64_t m_maxSize;

std::deque<WorkType> m_deque;

boost::mutex m_mutex;

boost::condition m_condSpaceAvailable;

};

Pipeline Stage

A pipeline stage holds the in-queue and out-queue. In-queue is where the work unit comes in, and out-queue is where result goes. The Run() function performs three steps that can be customized through inheritance.

// some code and comments are omitted to save space, download the

// source to see the full implementation

template<typename WorkType>

class CPipelineStage

{

public:

void InitQueues(

boost::shared_ptr<CBlockingQueue<WorkType> > inQueue,

boost::shared_ptr<CBlockingQueue<WorkType> > outQueue)

{

m_inQueue = inQueue;

m_outQueue = outQueue;

}

void Run()

{

FirstStep();

while(Done() == false)

{

Step();

}

LastStep();

}

virtual void FirstStep() = 0;

virtual void Step() = 0;

virtual void LastStep() = 0;

CBlockingQueue<WorkType> & GetInQueue() const { return *m_inQueue; }

CBlockingQueue<WorkType> & GetOutQueue() const { return *m_outQueue; }

bool Done() const { return m_done; }

void Done(bool val) { m_done = val; }

private:

bool m_done;

};

Linear Pipeline

The pipeline class allows stages to be added dynamically through AddStage(). Since all the Blocking Queues are owned by the pipeline, each added stage’s in-queue and out-queue will also be initialized through AddStage().

AddWork() allows a work unit to be added to the first stage. The work unit will be processed by all stages, and can be extracted through GetResult().

At last, Start() will simply kick off all stages concurrently by spinning up multiple threads.

// some code and comments are omitted to save space, download the

// source to see the full implementation

template<typename WorkType>

class CLinearPipeline

{

public:

void AddStage(boost::shared_ptr<CPipelineStage<WorkType> > stage)

{

m_stages.push_back(stage);

size_t numStage = m_stages.size();

m_queues.resize(numStage+1);

if(m_queues[numStage-1] == 0)

{

m_queues[numStage-1] =

boost::shared_ptr<CBlockingQueue<WorkType> >(

new CBlockingQueue<WorkType>()

);

}

m_queues[numStage] =

boost::shared_ptr<CBlockingQueue<WorkType> >(

new CBlockingQueue<WorkType>()

);

m_stages[numStage-1]->InitQueues(

m_queues[numStage-1], m_queues[numStage]

);

}

void AddWork(WorkType work)

{

m_queues[0]->Add(work);

}

WorkType GetResult()

{

return m_queues[m_queues.size()-1]->Take();

}

void Start()

{

for(size_t i=0; i<m_stages.size(); ++i)

{

m_threads.push_back(

boost::shared_ptr<boost::thread>(new boost::thread(

boost::bind(&CLinearPipeline<WorkType>::StartStage, this, i)

)));

}

}

void Join()

{

for(size_t i=0; i<m_stages.size(); ++i)

{

m_threads[i]->join();

}

}

private:

void StartStage(size_t index)

{

m_stages[index]->Run();

}

std::vector<

boost::shared_ptr<CPipelineStage<WorkType> >

> m_stages;

std::vector<

boost::shared_ptr<CBlockingQueue<WorkType> >

> m_queues;

std::vector<

boost::shared_ptr<boost::thread>

> m_threads;

};

Sample Usage

Now that the Blocking Queue, the Stage and the Pipeline are defined, we are ready to make our own pipeline.

As a user of the generic pipeline class, we need to define two things – the work unit, and the stages.

For demostration, I defined the work unit to be a vector of integers, and a stage called AddOneStage, which adds one of all element of the vector.

class CAddOneStage : public CPipelineStage<std::vector<int> >

{

public:

virtual void FirstStep() { /* omit */ }

virtual void Step()

{

std::vector<int> work = GetInQueue().Take();

for(size_t i=0; i<work.size(); ++i)

{

++work[i];

}

GetOutQueue().Add(work);

}

virtual void LastStep() { /* omit */ };

};

In the program, I will create a pipeline with three AddOneStage. So if I input a vector that goes through the pipeline, the end result would be the input plus three.

int main()

{

CLinearPipeline<std::vector<int> > pl;

pl.AddStage(boost::shared_ptr<CAddOneStage>(new CAddOneStage()));

pl.AddStage(boost::shared_ptr<CAddOneStage>(new CAddOneStage()));

pl.AddStage(boost::shared_ptr<CAddOneStage>(new CAddOneStage()));

pl.Start();

std::vector<int> work(100,0);

for(size_t i=0; i<10; ++i)

{

pl.AddWork(work);

}

for(size_t i=0; i<10; ++i)

{

std::vector<int> result = pl.GetResult();

std::cout << result[0] << std::endl;

}

pl.Join();

return 0;

}

Thoughts

CLinearPipeline essentially established a powerful concurrency framework for pipelining. It allows stages will be customized and added easily.

Although the work unit are passed by copy in the example, it can be changed to pointer easily to avoid the copy, nothing more than implementation details.

Problems such as handling protocol stacks can easily leverage this pattern because each layer can be handled independently.

Performance is best when the work among stages are evenly divided. You don’t want a long pole among the stages.

Unfortunately, the maximum amount of concurrency is limited by the number of pipeline stages.

Source

The source can be downloaded here.

Tools

Visual Studio 2008, Boost 1.40.

Reference

Timothy G. Mattson; Beverly A. Sanders; Berna L. Massingill, (2005). Patterns For Parallel Programming. Addison Wesley. ISBN-10: 0321228111

template<typename WorkType>

class CPipelineStage

{

public:

void InitQueues(

boost::shared_ptr<CBlockingQueue<WorkType> > inQueue,

boost::shared_ptr<CBlockingQueue<WorkType> > outQueue)

{

m_inQueue = inQueue;

m_outQueue = outQueue;

}

void Run()

{

FirstStep();

while(Done() == false)

{

Step();

}

LastStep();

}

virtual void FirstStep() = 0;

virtual void Step() = 0;

virtual void LastStep() = 0;

CBlockingQueue<WorkType> & GetInQueue() const { return *m_inQueue; }

CBlockingQueue<WorkType> & GetOutQueue() const { return *m_outQueue; }

bool Done() const { return m_done; }

void Done(bool val) { m_done = val; }

private:

bool m_done;

};