At my company, we develop a large software with fairly high concurrency. In general, asynchronous message passing is the choice for thread communication for its simplicity. When performance matters, we use locks and mutexes to share data among threads.

As the software grows, subtle bugs from dead-locks and race conditions are appearing around code that was designed with locks and mutexes.

I can say confidently that almost all of these bugs are caused by poor interface design or poor locking granularity. But I also feel that a well-designed thread-safe interface is extremely difficult to achieve.

Always Chasing The Perfect Granularity

To have a thread-safe interface, it requires far more than just putting a lock on every member function. Consider a supposedly thread-safe queue below, is this class really useful in a multi-threaded environment?

// thread-safe queue that has a scoped_lock guarding every member function

template <typename T>

class ts_queue()

{

public:

T& front();

void push_front(T const &);

void pop_front();

bool empty() const;

};

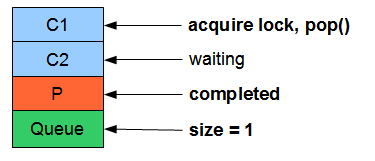

Unfortunately no. Here’s a simple code below where it falls apart. Say f() is called by multiple threads, if the the empty() check returns false, there is no guarantee that front() and pop_front() will succeed.

Even if front() succeeds, there is no guarantee that pop_front() will succeed. The ts_queue class interface is subject to race condition, and there is nothing you can do about it without an interface change.

//f may be called by multiple threads

void f(ts_queue<int> const &tsq)

{

if(tsq.empty() == false)

{

int i = tsq.front(); // this might fail even if empty() was false

tsq.pop_front(); // this might fail even if front() succeed

}

}

The problem is that mutexes are not composable. You can’t just call a thread-safe function one after another to achieve thread-safety. In the ts_queue example, the interface granularity is too small to perform the task required by f().

On the other hand, it would be easy to use some global mutex to lock down the entire ts_queue class. But when the granularity is too large, you lose performance by excessive locking. In that case, the multi-core processors will never be fully utilized.

Some programmers try to solve it by exposing the internal mutex to the interface, and pun the granularity problem to their users. But if the designers can’t solve the problem, is it fair to expect their users to be able to solve it? Also, do you really want to expose concurrency?

So in the process of designing a thread-safe class, I feel that I am spending majority of the time chasing the perfect granularity.

Full of Guidelines

In addition to the problem of granularity, you need to follow many guidelines to maintain a well designed thread-safe interface.

- You can’t pass reference/pointers of member variables out to external interface, whether it is through return value, or through an out parameter. Anytime a member variable is passed to an external interface, it could be cached and therefore lose the mutex protection.

- You can’t pass reference/pointers member variables into functions that you don’t control. The reason is same as before, except this is far more tricky to achieve.

- You can’t call any unknown code while holding onto a lock. That includes library functions, plug-ins, callbacks, virtual functions, and more.

- You must always remember to lock mutexes in a fixed order to avoid the ABBA deadlocks.

- There are more…

And if you are programming in C++, you need to watch out for all of the above while wrestling with the most engineered programming language in the world. 🙂

Final Thoughts

Locks and mutexes are just too complex for mortals to master.

And until C++0x defines a memory model for C++, lock-free programming is not even worth trying.

I will stop complaining now.