Couple weeks ago, I was trying to enhance an application with GStreamer to stream live audio (8k sample rate Alaw and 16-bit PCM) over UDP.

GStreamer’s pipeline framework is extremely powerful, and it is also poorly documented. I was able to get GStreamer to read from an UDPSrc without much effort, but the audio playback was choppy and would stop playing after a minute.

The choppy playback did not occur when the source was from a hard drive. So I concluded that the audio decoder in GStreamer was susceptible to bursty nature of the audio stream, and some buffering mechanism is necessary to ensure a smooth data rate.

Searching around the GStreamer developer forum, I found few poor souls posted similar issues with no solution.

So after several days of trial and error, I worked out a combo that solved my problem.

Lots of Queues

Disclaimer: I am a n00b with GStreamer, so my solution may be wrong or sub-optimal.

Here’s my GStreamer pipeline for 16 bit PCM audio at 8ksps streaming through port 50379 over UDP.

gst-launch.exe -v udpsrc port=50379 ! queue leaky=downstream max-size-buffers=10 ! audio/x-raw-int, rate=(int)8000, channels=(int)1 ! queue leaky=downstream max-size-buffers=10 ! audiorate ! queue leaky=downstream max-size-buffers=10 ! audiopanorama panorama=0.00 ! queue leaky=downstream max-size-buffers=10 ! autoaudiosink

For Alaw audio, the command is the following.

gst-launch.exe -v udpsrc port=50379 ! queue leaky=downstream max-size-buffers=10 ! audio/x-alaw, rate=(int)8000, channels=(int)1 ! alawdec ! queue leaky=downstream max-size-buffers=10 ! audiorate ! queue leaky=downstream max-size-buffers=10 ! audiopanorama panorama=0.00 ! queue leaky=downstream max-size-buffers=10 ! autoaudiosink

Result

As you can see, I am using queue to smooth out every pipeline level.

In addition to that, I am also buffering audio in my application and smooth out the UDP packet rate with a Windows Multimedia Timers.

So the sender (my application) and receiver (GStreamer) are both buffering to ensure the smoothest data rate.

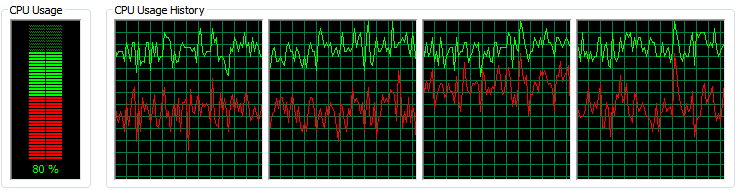

The result is excellent. The many layers of queuing allows a (fairly) high tolerance of bursting data. I am keeping this setup for now until I find something better.