For years, STL Map is the premium container choice for C++ programmers for fast data insertion, look-up and removal.

It uses a red-black tree, has elegant logarithmic properties, and guarantees to be balanced.

Therefore, Map is used very often in our product. Almost too often…

In TR1, Unordered Map has long been proposed. Boost has a cross platform implementation. VC9.0 also support the TR1 namespace.

It provides a powerful alternative to C++ programmers.

Penalty of Sorting

Besides fast data operation, Map also provides data sorting. As a refresher for data structure 101, a balanced binary tree will provide O(log n) for add/remove/search operations. In the case of red-black tree, it guarantees that the longest branch will not be 2x longer than the shortest branch. So, it is mostly balanced, but some operations can be somewhat longer than others.

But what if sorting is not necessary? Why would we heapify the whole tree on every add/remove operation? Can we do better than O(log n)?

TR1 Unordered Map is designed to tackle this problem.

C++ Hash Table

Most modern programming languages comes with some standard hash tables. For C++, well, it is still in a “draft” called technical report 1. As usual, the C++ standard committee spends most of its time on metaprogramming stuff, and neglect the simple and useful stuff.

The bottom line is that Unordered Map is the C++ hash table. It’s interface is very similar to Map. In fact, if sorting is not a requirement, simply changing your container map to unordered_map will be enough.

Unordered Map Could Be Right for You

Unordered Map offers O(1) for add/remove/search operations, assuming that the items are sparsely distributed among the buckets. In worst case, all items are hashed to the same bucket, and all operation becomes linear.

The worst case doesn’t happen often if the hash function is doing its job. If sorting is unnecessary, unordered map is faster than map.

But talk is cheap, let’s see some benchmark.

Speed Benchmark

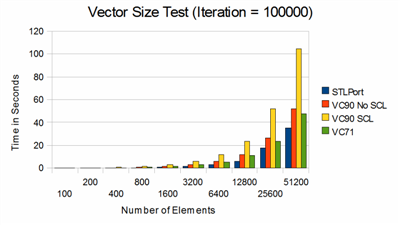

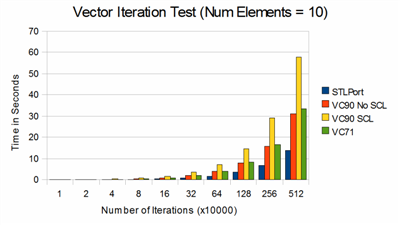

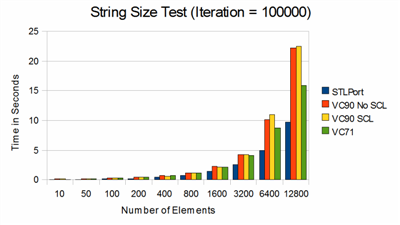

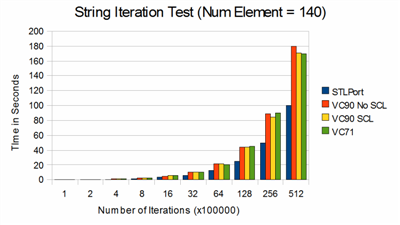

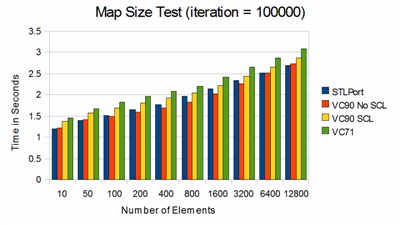

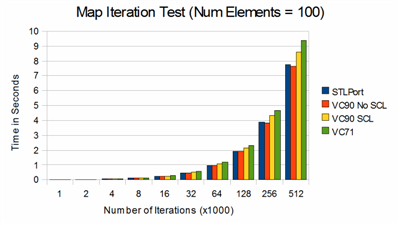

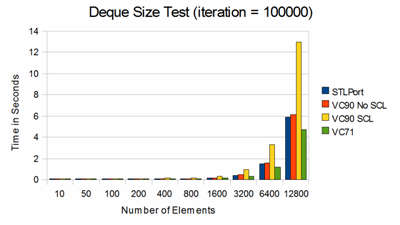

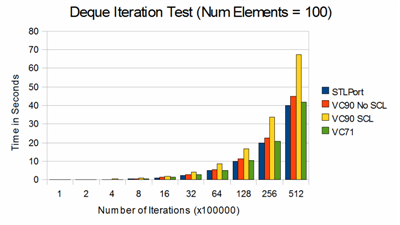

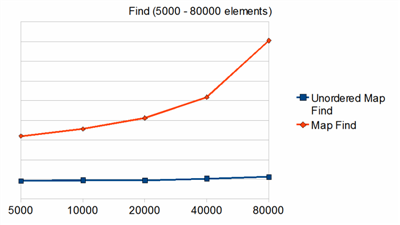

To test the containers, we insert a set of uniformly distributed random numbers into each container, and then one by one find the inserted numbers.

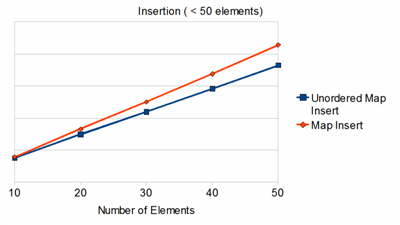

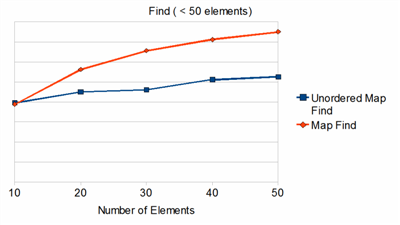

First, let’s test the performance of small container size under 50 elements. This is to find out if either of the container has any overhead associated for initialization.

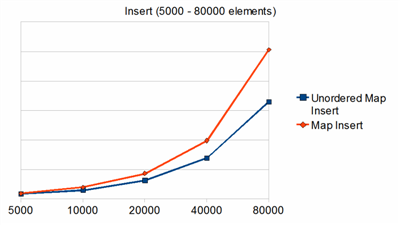

Next, we can try a much large data set to see how the container handle itself.

This is the penalty of sorting. Unordered_map runs at O(1), and it is unaffected the number of elements when the hash function is doing its job.

You can see that the search operation in Unordered_map is blazing fast. But hash tables are more than meets the eyes; the devil is in the details. We need further analysis before jumping into conclusions.

Looking A Bit Deeper

Unlike a balanced tree structure, hash table are somewhat unpredictable in nature. If the hash function is poorly suited for the given data set, it would backfire and result in linear runtime. Because of this nasty behavior, some programmers would even avoid hash table altogether.

There are numerous algorithm to optimize a hash table to avoid the worst case. In Unordered_map, there are two critical factors to consider- the max load factor and the hash function.

According to C++ TR1, the max load factor for Unordered_map should be 1.0. So if the average bucket size is greater than 1, rehashing would occur. VC 9.0 didn’t follow the standard, and uses 4.0 as the default load factor.

When Unordered_map grows beyond the allowed load factor, the number of buckets will change. In Boost, the programmer decided to increase the number of buckets by a prime number. In VC 9.0, the bucket size increases by a factor of 8 on each rehash.

For hash function, we can look at the integer hash function. Boost unordered_map follows closely with Peter Dimov’s proposal on Section 6.18 of the TR1 issue list. The hash function is defined as

for(unsigned int i = length * size_t_bits; i > 0; i -= size_t_bits)

{

seed ^= (std::size_t) (positive >> i) + (seed<<6) + (seed>>2);

}

seed ^= (std::size_t) val + (seed<<6) + (seed>>2);

VC90 uses a variant of LCG, the Park-Miller random number generator.

Trying for the Worst Case

Now that we know a bit more of implementation details, let’s see how bad the worst case is.

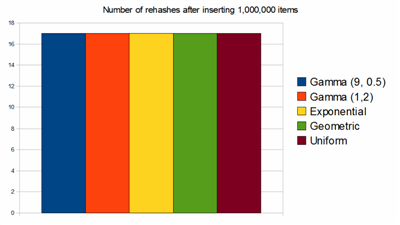

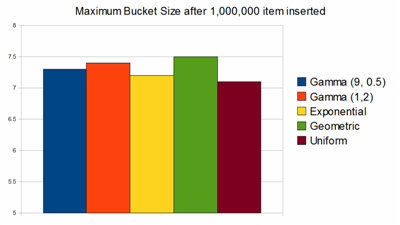

To do this, we can try to hash 1,000,000 random numbers. Unlike before, the random number will be generated from a non-uniform distribution – Gamma, Exponential, and Geometric. I particularly enjoy Gamma distribution because its shape can easily be skewed with shape and scale parameters.

There are two questions to find out from this test.

1. What is the maximum number of items hashed into a single bucket? In other word, what’s the worst case like?

2. Did the load factor of 1 cause more re-hashing? As we know, rehashing is very expensive and should be done the least possible.

Let’s see some results!

After 1,000,000 items inserted, it appears that the skewed data sample makes little difference to hash function.

Okay, I failed miserably in my attempt for the worst case. Choosing a skewed distribution only made a slight dent to the hash table. On average, the most overloaded bucket after 1,000,000 only has 7 items in there. In a balanced tree, O(log2(1,000,000) = 20. The hash function is definitely doing its job.

Conclusion

If sorting is unnecessary, Unordered_map provides a nice alternative to Map. If the container doesn’t change often, the performance gain with Unordered_map is even greater.

Don’t worry too much about the worst case of a hash table. The Boost implementation is rock-solid.

Avoid the VC9.0 TR1 Unordered_map because it does not follow standard. It is also a bit slower in comparison to Boost.

Pitfalls

The focus of this article is on speed. It is also necessary to compare the memory usage between Map and Unordered Map. I did some primitive testing and did not see a difference. But before jumping into conclusion, I need more time to think about the test setup. I will get to that when I get more time.

Source

The source and the spreadsheets can be downloaded here.

Tools: Visual Studio 2008, Boost 1.39, Window XP SP3