One of the most exciting feature to me in C++0x is Rvalue Reference. It is designed to eliminate spurious copying of objects and to solve the Forwarding Problem.

Rvalue Reference is a small technical extension to C++, but it could seriously increase the performance of existing C++ application for free or minimal changes.

GCC 4.3 and beyond has Rvalue Reference support. All it requires is a compiler option “-std=gnu++0x”, and all the supported experimental features will be enabled.

The C++ committee has a nice introduction to Rvalue Reference.

Too Many Copies

Rvalue Reference by itself isn’t too useful to the daily C++ programmers. Chances are the library writers will have the bulk of the work on optimizing their containers, and it will be mostly invisible to the end user. But nevertheless, the end user will need to supply two functions to take advantage of this optimization. They are Move Copy Constructor and Move Assignment Operator.

Consider a POD class that holds an index value for sorting, and a buffer that holds some data. It has an overloaded copy constructor and assignment operator to keep track of number of copying done on the object. Since it is designed to be used in a standard container, I will also supply a sorting predicate.

// global static variable to keep track of the number

// of times Pod has been copied.

static int Copies = 0;

// Plain Old Data

class Pod

{

public:

// constructor

Pod() : m_index(0)

{

m_buffer.resize(1000); // holds 1k of data

}

Pod(Pod const & pod)

: m_index(pod.m_index)

, m_buffer(pod.m_buffer)

{

++Copies;

}

// not the best operator=, for demo purposes

Pod &operator=(Pod const &pod)

{

m_index = pod.m_index;

m_buffer = pod.m_buffer;

++Copies;

}

int m_index; // index used for sorting

std::vector<unsigned char> m_buffer; // some buffer

};

// Sorting Predicate for the POD

struct PodGreaterThan

{

bool operator() (Pod const & lhs, Pod const & rhs) const

{

if(lhs.m_index > rhs.m_index) { return true; }

return false;

}

};

Now, we would like to utilize this data in a vector, and sort them.

std::vector<Pod> manyPods(1000000); // a million pod std::tr1::mt19937 eng; std::tr1::uniform_int<int> unif(1, 0x7fffffff); // assign a random integer to each POD m_index for (std::size_t i = 0; i < manyPods.size(); ++i) manyPods[i].m_index = unif(eng); // sort the million pods std::sort(manyPods.begin(), manyPods.end(), PodGreaterThan());

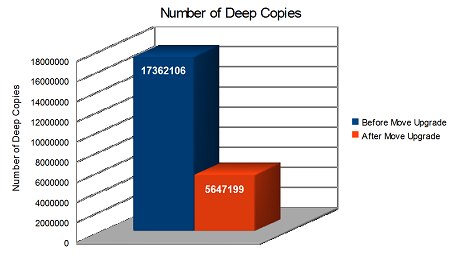

If you run this code in GCC 4.3.4, you will find out POD has been deep copied 17362106 times during the course of std::sort. That’s quite a bit of copies! Let’s see what Rvalue Reference can do for us.

Move Copy Constructor and Move Assignment Operator

Many of the copies in the previous example are likely to be temporary objects. Regardless of the sort algorithm, it is likely that it will spend much time swapping position between two items. And we know, the standard swap logic involves a temporary copy, and it has a very short lifespan. Rvalue Reference could be used to minimize this overhead.

Following Dave Abraham’s guideline on the move semantics.

A move assignment operator “steals” the value of its argument, leaving that argument in a destructible and assignable state, and preserves any user-visible side-effects on the left-hand-side.

We want to utilize the move semantics on temporary objects because they are short lived and side-effects are not a concern.

So let’s supply a Move Copy Constructor and Move Assignment Operator to the class Pod.

// move copy constructor

Pod(Pod && pod)

{

m_index = pod.m_index;

// give a hint to tell the library to "move" the vector if possible

m_buffer = std::move(pod.m_buffer);

}

// move assignment operator

Pod & operator=(Pod && pod)

{

m_index = pod.m_index;

// give a hint to tell the library to "move" the vector if possible

m_buffer = std::move(pod.m_buffer);

}

In these method, it is similar to the typical deep copy, except we are invoking std::move on the buffer. std::move might look like magic, but it works just like a static_cast from std::vector to std::vector&&. This is the crucial point of Rvalue Reference. By casting the vector to vector &&, it will invoke the Move functions of the vector automatically, if one exist. If the Move functions do not exist, it will fall back to the default non-move functions (deep copy). This is the beauty of the Rvalue Reference overloading rule.

GCC 4.3.4 vector is “Move Ready”. Here’s an example of their Move Assignment Operator.

#ifdef __GXX_EXPERIMENTAL_CXX0X__

vector&

operator=(vector&& __x)

{

// NB: DR 675.

this->clear();

this->swap(__x);

return *this;

}

#endif

*On a side note, Line 6 is very interesting because it gets around a bug that is caused by a delay in the deletion of temp object.

Speed Up after the Move Upgrade

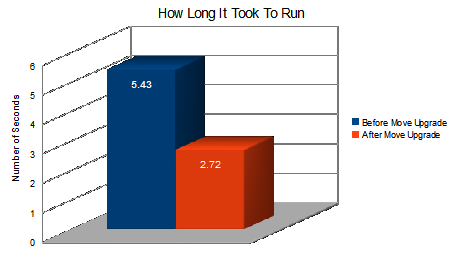

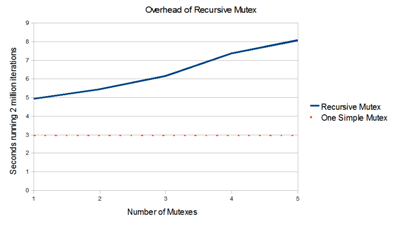

Now we run the same code again after supporting Move Copy Constructor and Move Assignment Operator in Pod.

By simply supplying a Move Constructor and Move Assignment operator to Pod, the sort routine runs twice as fast. That also implies that we’ve been wasting half the time in the sort routine moving temporary objects around.

Conclusion

Rvalue Reference will provide a nice performance gain to users of STL containers.

To end user, all that’s required is a Move Constructor and Move Assignment Operator.

Thoughts

It would be even nicer if they can supply default Move functions to all objects. It appears that it has been proposed. I look forward to see its progress.

Source

The source can be downloaded here.

Tools: GCC 4.3.4, Cygwin 1.7, Window 7 64bit